Georgia Brennan-Scott is exploring living labs methods and practices. Her research will inform the legacy of the INCLUDE+ network, hopefully culminating in a living lab of our own.

Asset-based community development (ABCD) rejects a needs-oriented approach to community development i.e. assessing communities based on what they are lacking and where they are failing. ABCD calls instead for a recognition of the assets inherent in any community—the people and the connections between them, their knowledge and skills, and physical assets like the land. ‘Start with what’s strong, not with what’s wrong’ is the oft-repeated phrase of Cormac Russell, proponent of ABCD in the UK. Russell is critical of the way institutions imagine service-users as clients, wishing to instead empower them as citizens. He implores us: put citizens at the heart of their community and its transformation.

There’s a lot to learn from ABCD. Asking different questions is a powerful way to reframe conversation. By engaging with citizens as capable individuals with ideas and expertise, the uneven dynamic between ‘helping’ institutions and ‘helpless’ communities can be redressed.

ABCD has been criticised for showing a fundamental distrust of institutions, placing the onus of structural failures on those crushed by them. Equally, ABCD can be humbling for those within an institution. To echo Cormac Russell, engaging with community assets might look like recognising our own redundancy. Rather than focusing institutions’ deficiencies or downright rejecting them as incompetent, there is value in recognising the power of community-led solutions to community-felt problems.

Mary Anne MacLeod and Akwugo Emejulu provide a critical lens into how ABCD is interpreted in many ways by practitioners. Their perspective comes from a study conducted by speaking to practitioners of ABCD in Glasgow.

MacLeod and Emejulu criticise how asset-based community development reflects a distrust of institutions, arguing that this deep-rooted scepticism manifests in a neoliberal redirection of responsibility. They make the case that by decrying the value of institutions, communities’ challenges are individualised without acknowledging the inherent, recurring and structural failures from which these challenges result.

‘The [welfare] state can be a cumbersome, bureaucratic and self-serving institution that undermines individual liberty and innovation. But it can also be a key guarantor and protector of equality and rights which makes individual liberty possible and meaningful. For community development, the state is both these things simultaneously.’

(Akwugo Emejulu, 2013)

The role the state plays in protecting equality is not to be underestimated, and cannot be enacted instead by communities. However, ABCD posits that institutions are unable to meaningfully intervene without meaningful participation from communities. ABCD is something which can be employed selectively with and by institutions to allow for collaboration between communities and institutions (perhaps through a third-sector and/or community-based organisation) to fundamentally transform a community landscape.

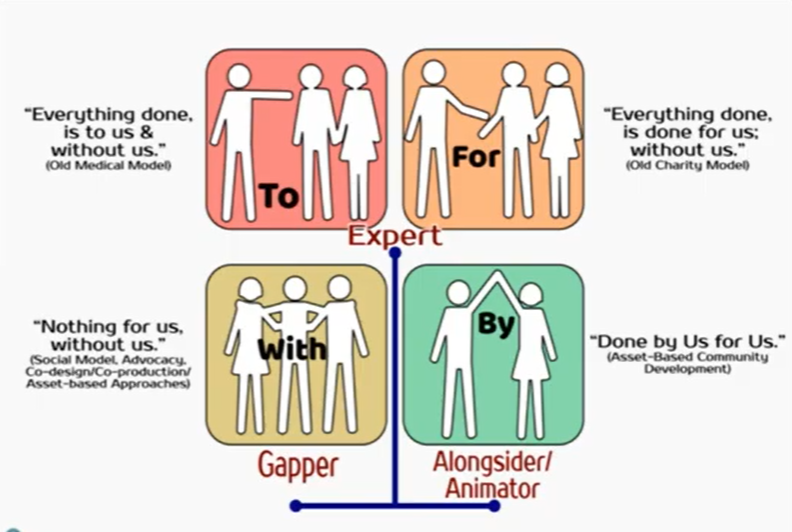

Cormac Russel states that institutions are limited in their ability to connect with communities. ABCD makes the case that for change to be empowering, the community needs to be involved in defining, developing and delivering the solution. The precise struggles of a community are unlikely to be accurately or fully reflected in the data led by institutions. In fact, it will likely reflect our priorities and biases. We must be prepared to discover that we do not know best what a community needs.

‘When we do change to people, they experience it as violence. But when people do change for themselves, they experience it as liberation.’

Rosabeth Moss Kanter

Further, we must pay attention to the language we use. We are condemning communities in framing them by ‘their’ failures (e.g. drug-ridden, underprivileged, disadvantaged). By adopting the ‘what’s strong, not what’s wrong’ mentality, we can see that communities have much that we can learn from and build upon.

A refreshing perspective can be found in a webinar from the West Africa Civil Society Institute (WACSI). Civil society leaders share how ABCD can be applied in a West African context. One of the chief distinctions is how Omolara Balogun, Head of Policy Influencing and Advocacy, addresses institutions as part of communities. By comparison, there is an othering in the way Cormac Russell and John McKnight (the originator of ABCD) talk about employing ABCD. Balogun offers leaders the tools to employ asset-based thinking in their own work, extending the cup-half-full mindset to how they view themselves. Balogun also talks about how working with donors shapes the work of West African civil organisations. She acknowledges that donors and institutions come in with their own agendas and their own ideas of what needs to be solved. If you are able to show funders what’s strong: what you can do and what you have already done, they are more likely to offer their support. This West African perspective serves as a reminder that where power (and money) is held, shapes how ABCD can be applied.

For me, this perspective shows how a ‘what’s strong’ mindset can be employed by any element of the community development chain. This brings to mind another challenge posed by Russell: stop thinking about what role you will play and instead ask what you have to offer.

This directs me to think not about the role of our living lab but about what we have to offer. This will ultimately define our role.

Sources:

Sustainable community development: from what’s wrong to what’s strong | Cormac Russell | TEDxExeter

Principles of Asset Based Community Development

WACSI Asset-Based Community Development (ABCD) webinar

Mary Anne MacLeod & Akwugo Emejulu (2014) Neoliberalism With a Community Face? A Critical Analysis of Asset-Based Community Development in Scotland, Journal of Community Practice, 22(4), 430-450, DOI: 10.1080/10705422.2014.959147